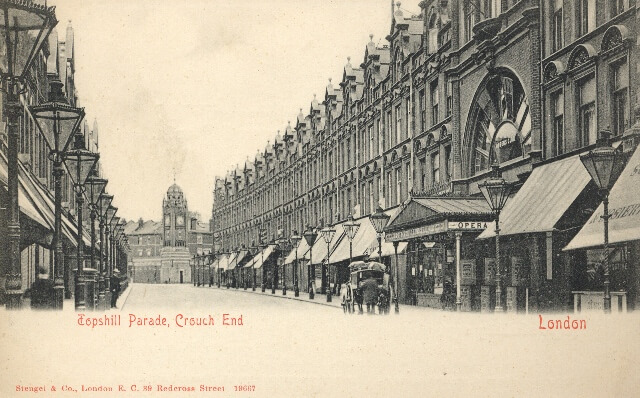

Crouch End, today, provides no obvious evidence that it was once the location of a theatre. You won’t see a huge auditorium that has been through various incarnations such as cinema, bingo hall, or space used for worship. The evidence is there though, at 31, Topsfield Parade on Tottenham Lane nestled in amongst the shop units. The restored semi-circular glass window is recognisable from old images and a new glass canopy echoes the structure that previously covered the whole pavement.

A burgeoning middle-class

The purchase and demolition of Topsfield Hall in 1894 paved the way for developers James Edmondson and John Cathles Hill to build houses. However, neither stopped there, seeing an opportunity to augment the community with shopping parades and the social facilities required by the burgeoning middle-class population. JC Hill notably built the Queens Hotel in Tottenham Lane while Edmondson was the developer responsible for the Crouch End Opera House.

Marlene McAndrew takes up the story in her HHS book, Lost Theatres of Haringey. Edmondson began in 1894 by submitting plans to the Hornsey Urban District Council for “a public building and warehouse” at 31 Topsfield Parade on Tottenham Lane “for use as a club, gymnasium, lecture hall and for general public purposes”. But by the following year the plan had been amended and the building was now described as “Crouch End Athenaeum, The Hippodrome, Tottenham Lane. Amended plans for Athenaeum”.

Ambivalent attitudes

At least one commentator reported the community’s ambivalent attitude to the theatre pointing out that there were those “who had hoped that at last the district of Hornsey was to have a public hall worthy of the neighbourhood..[and who would]…regret that Messrs Edmondson and Son did not adhere to their original view.”

It seems that some Crouch End residents had looked forward to having a public amenity, a location more akin to a community space that could support the thriving social life of the village by providing a base and venue for the many social, political and sporting clubs that were flourishing in the area. Given this initial lack of certainty about what was needed or wanted from the facility, the theatre’s relatively short-lived existence and its inability to firmly establish itself seems unsurprising.

Edmondson recruited Frank Matcham, to transform the hall into a theatre. Matcham is now recognised as the most eminent theatrical architect of the time, having designed buildings like the Lyric Theatre in Hammersmith and the Grand Theatre, Blackpool. He also went on to design the Wood Green Empire.

The opening

The theatre opened on 27th July 1897 as the Queens Opera House. The narrow frontage on Tottenham Lane gives no clue as to the capacity of 1200 in the auditorium, although this wasn’t a large theatre by the standards of the time and the theatre was often referred to as small or “cosy”. Also unusual was the absence of a gallery, the space was used instead to build two floors that were available for hire. The theatre was heated with radiators, and equipped with a kitchen, smoking and refreshment rooms as well as having eight dressing rooms for the performers.

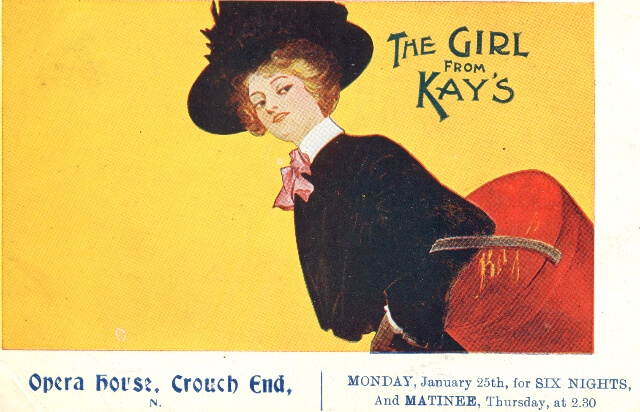

The first production staged at the Opera House was The Geisha, which was generally well-received. This was the first of many popular productions that were doing the rounds at the time, and by 1899 stars of the day like Mrs Patrick Campbell, Lillie Langtry and Ellen Terry all performed there and weekend performances were booked up over a week in advance. Unfortunately tour managers began charging west end rates for suburban theatres. These increased costs at such a small theatre made providing a consistent programme of high calibre productions unsustainable. The hope of making the Queens Opera House the most important theatre in north London began to ebb away.

Varied uses

The first decade of the twentieth century saw the theatre go through a series of licensees and managers, short lived periods of success and a three year closure from 1904 because of a devastating fire. In 1910 silent film showings were added to the programme but audiences continued to decline, diverted by the Grand in Islington and the Finsbury Park Empire with its superior public transport links. In 1928, live performances came to an end when the theatre was converted by British Gaumont into a cinema. This ran until 1942 when the building was again rendered unusable by a serious fire.

The building’s subsequent uses were varied. They included a dance school in the late 1940s and, from the late 1950s its use by Grattans Mail Order Company. By the late 1990s developers had gone back to the building’s origins for inspiration, having acquired planning permission for a gym on condition that the building was dealt with in a more sensitive way than it had been, and was harmonised with Edmondson’s shopping parade. The frontage was restored, reinstating the semi-circular glass window and part of the canopy. Its current use as a gym was part of the original Edmondson plan so the building can, in part at least, be seen to have been returned to its roots.

References

Marlene McAndrew, Lost Theatres of Haringey, HHS 2007

Ben Travers, The Book of Crouch End, Barracuda Books, 1990

Roy Porter, London A Social History, Penguin, 1994

ArthurLloyd.co.uk

Image credits

Hornsey Historical Society