We resume our 2022 series on Church buildings which have changed their function with this second article.

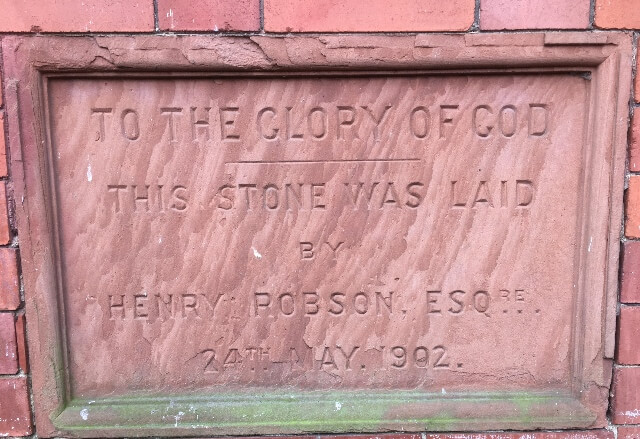

On the corner of the Broadway and Princes Avenue N10 stands an imposing building with a corner tower surmounted by a copper spirelet, white flint walls, large tracery windows and Ruabon brick mouldings round the doors. The signs outside reads, ‘Miller & Carter Steakhouse’ but on the east wall is a tablet stating, ‘To the Glory of God. This Stone was Laid by Henry Robson Esq. 24th May 1902’. What on earth has been going on?

How it all started

In 1896 builder James Edmondson bought The Limes and Fortis House estates and created the Muswell Hill townscape which is instantly recognisable today. As a Nonconformist he was keen to see churches built in the suburb he was creating. He sold a prime site on his newly created Broadway (1897) for half its commercial value to support the building of a Presbyterian church.

The building takes shape

The new church had to be large enough to accommodate the growing number of worshippers and to cost no more than £7,000. The design competition was won by father and son George and Reginald Baines who designed a church to stand out and make an impact at the corner of Edmondson’s prestigious Princes Avenue, with a view towards London from the church’s front porch. Even in Edwardian times prices escalated unexpectedly – the contract sum of £6,932 rose to over £12,000 by completion in 1903. In 1898 a church hall was built at the rear on the Princes Avenue side.

Changing times

In the 1960s leaders of Muswell Hill’s Presbyterian and Congregational churches started drawing up plans for possible union. This became a reality in 1972 when the denominations joined together nationally as The United Reformed Church. Afterwards the Broadway and Tetherdown premises were used alternatively for three months at a time. Significantly, in 1973 Muswell Hill was declared a Conservation Area because it was, ‘a remarkably well preserved example of an early Edwardian shopping centre and its completeness and townscape quality is probably unrivalled in any inland town’.

What to do with the redundant church building?

It soon became clear to both congregations that although the Tetherdown church was not as centrally placed, accommodation there suited current church and community activities far better than at the Broadway church. In 1975 they agreed to cease using the Broadway church and to alter the Tetherdown premises to meet its new role. Church leaders favoured selling the Broadway building for much needed cash even though it might be demolished. They involved Haringey Council officers who thought that maybe the building could become a library.

The battle from the mid-1970s

The threat of demolition hung over the Broadway building for years amidst a furore of protests from local groups, including HHS, ably represented by its Conservation Officer, Bridget Cherry, an architectural historian, now HHS Vice President. She stated, ‘The church is certainly one of the most original and distinctive of the non-conformist churches that survive in this part of London’. She managed to get the building on to the Department of the Environment’s Haringey list, hoping that this would safeguard it. The Broadway Church Action Group (BROACH) was set up in 1975. It believed that redevelopment of the site would have an adverse impact on the commercial life of Muswell Hill and claimed that higher rents and rates would result if the church site was developed, leading to more closures.

Vigorous protests

In March 1976 Haringey Council announced that the building would be demolished and replaced by a 4 storey block, comprising ground floor shops, first floor offices and 2nd & 3rd floor flats. The resulting vigorous protests were a journalist’s dream and miles of newspaper print rolled of the presses. The arguments were that, i) the church was in the centre of Muswell Hill’s recently designated Conservation Area; ii) Muswell Hill was a fine example of Edwardian town planning; iii) the building formed a key element of this Edwardian scene and, iv) if the church was demolished it would set a precedent for the relentless erosion of the surrounding shops and houses.

Local groups stated that this architectural gem must not be lost, if not a church, then it should be put to community use as a library, concert hall, theatre or arts/exhibition centre. Support came from Sir John Betjeman, Sir Hugh Casson, Sir Nikalous Pevsner and Yehudi Menuhin. The case to preserve the building was strengthened when Grade II listing was granted.

The battle is not over yet

The Secretary of State for the Environment planned to hold an Inquiry in Hornsey Town Hall, Crouch End, in late 1977 but this was delayed until May the following year. Statements were written by the Trustees of the United Reformed Church and by each local protest group including HHS. The Trustees argued that it was their duty to sell and that they did not believe the building was worth preserving.

Bridget Cherry’s statement covered the architectural, conservation and social arguments, drawing attention to the importance of Nonconformity in the area as an historical force which should remain suitably commemorated. She added, ‘Whilst the Presbyterian Church is outstanding in itself its interest lies also in it being one of the most prominent of this group of buildings which enlivens the architectural scene in this little altered Edwardian suburb’. HHS knew it was not possible to demand the preservation of all nonconformist churches but in an age of rapid change it was important to preserve the best examples of buildings of each period.

The following year the Department of the Environment Inspector summed up all the evidence submitted to him and judged that the former church well merited its status as a listed building, demolition was not justified, neither was erecting a building quite out of character with the Broadway buildings.

The former church is saved … but for what purpose?

All this time the United Reformed Church had borne the cost of maintaining and insuring two buildings, a considerable draining on meagre funds. BROACH wanted Haringey to back conversion of the church into a concert hall and recording studio. From 1985 to c.1992 Haringey used the building as the Council’s Social Services offices. Staff found the accommodation unfit for purpose. Would it become a community centre? Financial backing was not forthcoming. Once more this former church was left unoccupied.

The church battle is not yet over …

In 1995, 22 years after the congregation had left, Taylor Walker Brewery proposed opening a Firkin pub, particularly popular with young people. The company intended spending £750,000 on refurbishment. The furore started anew amongst the residents of nearby streets who were concerned about late night noise and an influx of cars. BROACH supported Taylor Walker reasoning, ‘This application is the first serious proposal to use the building in a way which will guarantee that it survives. If it is not used in a way to raise enough money to keep it maintained, it will fall into disrepair and be demolished. Haringey planning chiefs must impose appropriate conditions on the pub to ensure no problems.’

Others were not convinced and the campaign co-ordinator told the Hornsey Journal, ‘We’re not going to take this sitting down. We will fight on. The scale of the proposal is gigantic. It will be detrimental to our suburb. We already have chronic parking problems. The noise will explode. People come here by car as Muswell Hill has no tube. We’re not a tourist spot like Brighton’.

What of the future?

Nevertheless, in 1997 the former church was converted into a pub. In recent years O’Neills Irish pub has been in residence. Presently it is a steakhouse. What lies in the future for this 119 year old former church? Only time will tell but there may well be more furores ahead. One thing is certain – a small local history society can pack a punch when the chips are down.

Image credits

Hornsey Historical Society