A 1972 series of Hornsey Journal articles by Ian Murray, first Chairman of Hornsey Historical Society and Haringey Borough Archivist. The HHS gratefully acknowledges the kind permission of Archant/Ham and High for this reproduction

For 12 years, from 874, Hornsey was part of the Danelaw, that part of the country under the control of the Danes, until it was liberated by Alfred the Great. The Thames valley was repeatedly ravaged by the Vikings and the remains of a Viking ship were discovered in the Lea at Tottenham in 1901.

The origin of Hornsey as a distinct district is rooted in the Anglo-Saxon settlement. Two institutions, one of which survived until recently, and the other still surviving, can be traced back to this remote period. One is the manor and the other is the parish. No one knows exactly when the parish, as a unit of ecclesiastical organisation, first originated. The formation of a parish seems to have been a continuous process from the time of the conversion to Christianity (597AD) for, as bishoprics were founded, churches would also be founded to serve the settlements in the diocese and priests appointed.

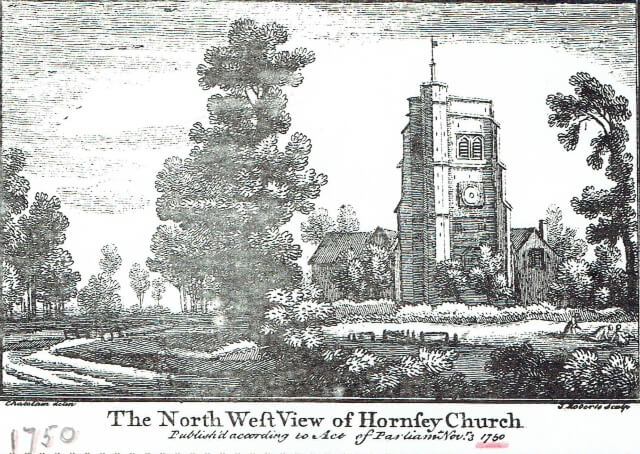

At the same time, individual lords’ built churches on their estates or manors so that the parish and manor, from an early date, tended to be extensive. In the case of Hornsey the church was quite possibly founded quite early as it was near to the seat of the Bishop.

Large estate

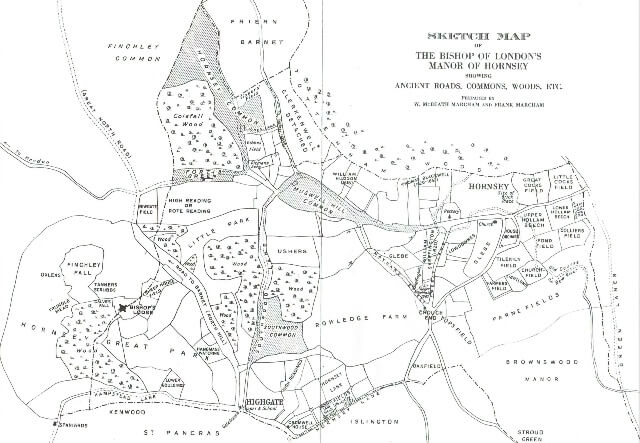

There is, in fact, a close connection between the Bishop of London and Hornsey, for the former was also the Lord of the Manor of Hornsey: a bishop was at that time both an ecclesiastical and a temporal lord and the holding of large areas of land was not inconsistent with his position in the Church.

It is difficult for us to visualise the manorial system or the social assumptions which made it operate. In medieval times the manor was the basis of rural England. It was a large estate controlled by the lord of the manor who held it of some higher authority (ultimately of the king) in return for allegiance and military service. Part of the manor, known as the demesne, was the lord’s own land. The rest was held by the tenants in return for labour services on the demesne, or money rent, or sometimes both. The tenants had rights such as those of grazing their animals on the commons, gathering fuel and feeding pigs in the woods.

Powerful lords

The essential point was that the land was not held in compact individual holdings but in strips scattered throughout large open fields, usually three in number. One or more of these were left fallow every third year, in order to restore fertility. Even the demesne was often dispersed in strip form throughout the fields. Agriculture was carried out communally on a co-operative basis. Oxen would be pooled at the ploughing season. After the harvest the common fields would be thrown open for the animals of the tenants to feed upon the stubble.

How this system originated is uncertain but it seems likely that in the troubled and insecure times of the Viking invasions, the majority of the peasants, who eked out a living by subsistence agriculture, were tempted to submit to powerful lords in return for security and protection. Even before the Norman conquest the Lord of the Manor of Hornsey was the Bishop of London who held also a large part of Middlesex stretching in a broad semi-circle, from Stepney to Fulham.

Three manors

The earliest document which states positively that Hornsey was held by the Bishop of London is dated as late as 1294, when Richard de Gravesend, Bishop of London, was summoned to explain by what authority he held his land and exercised his rights over it. ‘And the Bishop comes and says that Hakeneye and Haringeye (Hackney and Hornsey) are members of Stebenhethe (Stepney)…and…thathe and all his predecessors from time immemorial have held…the same vills’. (villages)

Domesday Book, compiled in 1086, does not mention Hornsey by name, and it is clear from this later document that it does not do so because it was considered a part of the Lordship of Stepney. The evidence of Domesday suggests that there were three manors within Hornsey, two held of, and the main directly by, the Bishop of London. The problem is that references in Domesday Book are not arranged by place but by landholders and it is necessary in the case of Hornsey, which formed part of a larger group, to reconstruct the manorial structure from internal evidence.

LAND OF THE BISHOP OF LONDON

“In Osuluestan [Ossulstone] Hundred the Bishop of London holds Stibenhede [Stepney] for 32 hides. There is land for 25 ploughs. To the demesne belongs 14 hides … There are 44 villeins each on 1 virgate … There [are] 4 mills rendering £4 16s. less 4d. [There is] meadow for 25 ploughs; pasture for the cattle of the vill [yielding] 15s; wood[land] for 500 pigs and yielding 40s. The whole is worth £48… This manor belonged and belongs (fuit et est) to the bishopric.”

Taken from the Domesday Book as set out in the Victoria County History, Middlesex, Vol 1, page 120

Population

The total held within Stepney by the Bishop amounted to about 3,000 acres of arable land, 1,700 acres of demesne land and the rest pasture, meadow and woods supporting 500 pigs. The whole was worth £48 yearly, two pounds less than at the time of Edward the Confessor. The villein population was 104 with the addition of their families. It is obviously difficult here to distinguish between Hornsey, Hackney and Stepney, but there is one reference which can only be to Crouch End.

Identified

William the Chamberlain, presumably an official of the King’s household, held of the Bishop 200 acres of land. *This was probably the Manor of Topsfield in Crouch End, for descendants of the same William were still living in the area at the end of the 13th century when the location can be identified.

LAND OF THE BISHOP OF LONDON

“In the same vill William the Chamberlain holds of the bishop 11⁄2 hide and 1 virgate. There is land for 11⁄2 plough. There [is] in demesne 1 plough, and there can be 1⁄2 more. *There [is] 1 villein on 1 virgate, and 6 bordars on 5 acres*. In all it is worth 30s… Bishop William held this land in demesne on the day on which King Edward died.”

Taken from the Domesday Book as set out in the Victoria County History, Middlesex, Vol 1, page 120 and confirmed as * Crouch End* (see reference above) in the Victoria County History, Middlesex, Vol.VI, page 107

Sub-manor

The other sub-manor, distinct from the manor of Hornsey proper, was the Prebendal Manor of Brownswood, which extended south from the Hog’s Back and encompassed the present districts of Stroud Green and Finsbury Park. It intruded well into modern Stoke Newington: this area, known as South Hornsey, remained part of the parish as late as 1896.

Glossary of words relating to the manorial system

bordars – the lower class of peasants, also called cottars; demesne – the property farmed outright by the lord; peasants worked on this for a specified number of days a week; hide – from the Anglo-Saxon word meaning ‘family’, a land-holding, equivalent to approx. 120 old acres (30 modern acres) depending on the quality of the land. A hide was the basis for tax assessment; vill – a village; villein – a feudal tenant subject to the lord of the manor and paying him dues and services in return for land; virgate – reckoned as the amount of land that a team of two oxen could plough in a single annual season. It was equivalent to a quarter of a hide, so was nominally thirty old acres.

For the story of how the medieval parish of Hornsey was changed permanently read HHS’s very recently published 50th anniversary publication, The Hornsey Enclosure Act 1813 by David Frith.

Image credits

Hornsey Historical Society