A 1972 series of Hornsey Journal articles by Ian Murray, first Chairman of Hornsey Historical Society and Haringey Council Archivist. The HHS gratefully acknowledges the kind permission of Archant/Ham and High for this reproduction.

Although Highgate was the most important village by the late 17th century, and probably before, it lay only partly in Hornsey. Part of it lay in the parish of St Pancras, and as far as manorial structure is concerned, Highgate village was shared with the Manor of Cantelows, which also included Kentish Town, a sub manor of the Manor of St Pancras created in the late 13th century.

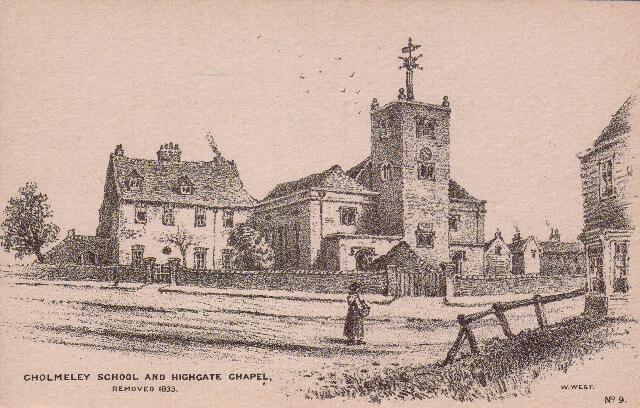

Since parochial and manorial boundaries intersect Highgate, and these boundaries date from before the Conquest, it is reasonable to suppose that Highgate was not an original settlement and developed at a recent date. It did not itself become a parish until 1833. This is all the more surprising in view of its location, probably not densely forested and with an adequate water supply available from wells.

Live deer

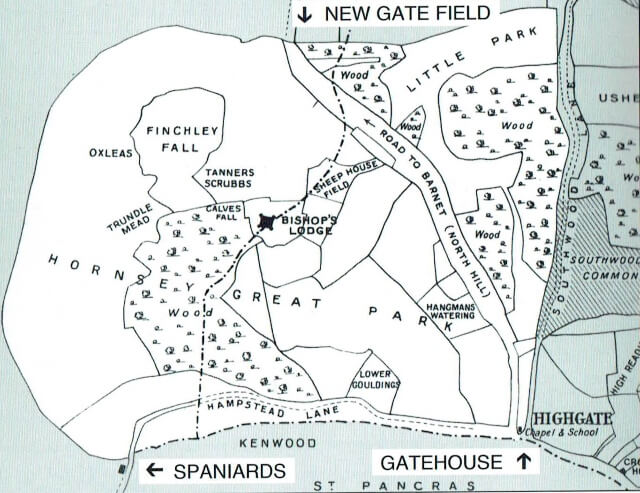

The reason may well be that the district was probably at an early date dominated by the Bishop of London’s hunting park, a large tract of country extending from Highgate Gate House over to the Spaniards Inn, East Finchley and nearly to Muswell Hill, which was enclosed and stocked with deer for the Bishop’s sport. In 1241 for example, there is a record of a gift of ten live deer in ‘The Park of Haringeye to the Earl of Pembroke from Henry III’, who was administering the park pending the appointment of a new bishop.

As we saw earlier, the Bishops of London held a great stretch of country north of the Thames from before the Conquest. It may well be that the establishment of the park and the drawing of the parish boundaries were contemporaneous and that there was no pre-Conquest settlement in Highgate for this reason.

Demolition

Within the park there existed until the 15th century, a hunting lodge known as the Bishop’s Lodge, which was one of the episcopal seats. It stands within what is now Highgate Golf Course and the outline of the moat is plainly visible from the air. It is located also on the very borders of Hornsey and Finchley which would suggest that it was placed strategically between the two so that the Bishop’s officers could oversee operations in both manors.

John Norden writing about a century after the demolition of the Lodge, when the ruins were still visible, mentioned, ‘a hill or fort in Hornsey Park, and so-called Lodge Hill, for that thereon for some time stood a lodge, when the park replenished with deer’. He goes on to say, ‘but it seemeth from the foundation it was rather a castle than a lodge, for the hill is at this time entrenched with two deep ditches now old and overgrown with bushes; the rubble thereof as brick, tile, and Cornish slate are in heaps yet to be seen, which ruins are of great antiquity as may appear by the oaks at this day standing, above one hundred years growth, upon the very foundation of the building’.

Norden’s remark, that it appeared to be a castle rather than a lodge, is interesting. The building stood at about 350 feet above sea level, very near to London and placed between two main roads out of the City, but it would be difficult to say whether the lodge ever had a military function. At all events it was a substantially built structure and like all medieval secular buildings combined security with domesticity. Only excavation will tell us more about it.

The name of Highgate itself betrays its origin. It does not mean what it appears to mean, the high gate, but rather the hedge gate, or the entrance to the gate round the park, from the old English ‘heag’ or ‘heie’, a hedge (as in Hornsey) and ‘geat’ or gate. After about 1540 the word ‘hill’ creeps in, referring to its elevation and one form of the name is Highgate-on-the-Hill. The gate signified a toll gate, for during the 14th century the North Road out of London ran up Highgate Hill and through Bishop’s Park (part of which is now North Hill) over Finchley Common to Barnet. This gradually replaced an earlier route up Hornsey Rise, through Crouch End and up Muswell Hill to Fortis Green, which had proved impassable, like many roads at the time, in wet weather.

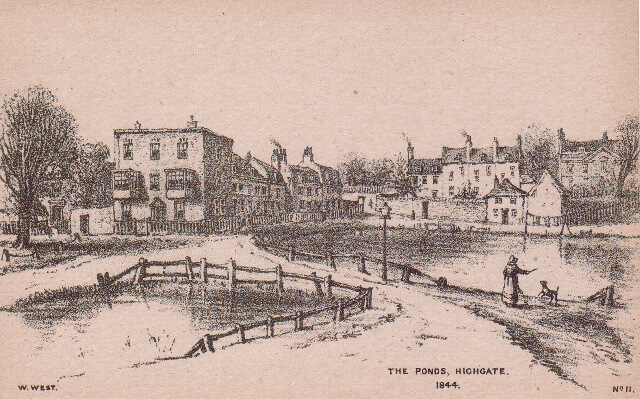

Gravel from the pond

The tolls collected from travellers going through the Bishop’s park form an important item in the surviving accounts of the Bishop’s Reeve, as in September 1283. In 1354 the Crown granted this right, known as a Pavage Grant, to two Highgate men, John Lovell and William Smyth for one year. How the Crown was able to do this when it did not possess the right, which was vested in the Bishopric, is uncertain, but we find the same thing happening in 1364 when William Philippe was granted the same right for a year, that is to take tolls for the repair of the road from Smethefeld to Heghegate. He had apparently been doing this at his own expense. ‘We highly recommend’, the grant says, ‘the pious motive which … you continually exert … in the support of that way in wood and sand … at your own cost’.

The grant enabled Phillipe to charge 2d. for a cart shod with iron, 1d. for a cart not shod, and ¼d. for a pack horse, by the week. It has been suggested that William Philippe dug the gravel for this purpose from the top of Highgate Hill thus forming a pond which lay in what is now Pond Square. The importance of these tolls was considerable and a good investment. Sir John Wollaston paid £449 for them in 1650.

Image credits

Cholmeley School and Highgate Chapel, and The Ponds, Highgate by William West/HHS; The Bishop of London’s Manor of Hornsey, Sketch Map Prepared by W McBeath Marcham and Frank Marcham, 1929