As the Old Schoolhouse has been closed, we’ve been running an occasional series sharing extracts from HHS publications. Ivy-Mantled Tower was published in 2015. Its author, Bridget Cherry, is Vice President of HHS and an architectural historian who worked for many years as author and editor of the Pevsner Architectural Guides. This is an extract from Chapter 2 Interpreting the Building: The Evidence for the Medieval Church.

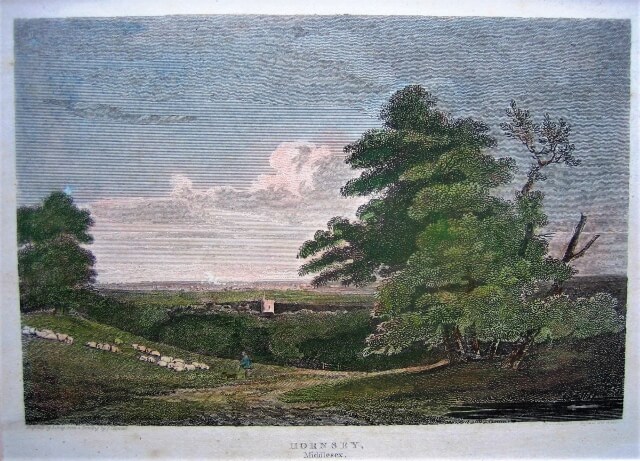

What can one deduce about the nature and date of the medieval church? While descriptions, drawings and paintings provide a picture of the appearance of the church from the mid eighteenth century onwards, it is more difficult to establish its earlier history. Land at Hornsey, including a hunting lodge at ‘Lodgehill’, Highgate, was among the early possessions of the medieval bishops of London, but early documentary references to the church at Hornsey are frustratingly thin.

The date of acquisition of Hornsey by the Bishop is unknown. It appears that it was grouped in the records with Stepney, and so was not recorded separately. It is not mentioned in Domesday Book and, like other bishop’s manors in Middlesex, its name does not appear in a list of Middlesex churches made in 1244–48. The first reference is in the taxation list of 1291, where a priest at Hornsey is mentioned, but a parish church may have existed much earlier.

The building history

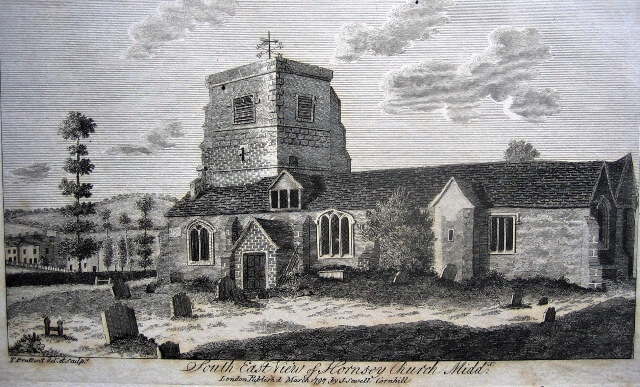

What evidence is provided by the artists? No plan survives, but their views indicate a church that had grown gradually to meet changing requirements, as was common with medieval parish churches. The older churches that survive in many former Middlesex villages show that by the end of the Middle Ages, the basic provision of a chancel for the clergy and a nave for the laity had frequently been supplemented by additional chapels, side aisles and a tower.

The eighteenth-century views of Hornsey show that the body of the church had two parallel roofs, one covering the nave and chancel, the other covering the long south aisle which extended the whole length of the church and embraced the west tower. On the north side there was no aisle, suggesting that the fabric of the north wall could have survived from an older building. Views that show the church from the north provide few clues, apart from the fact that there was a small north doorway, as was common in medieval churches, which survived the alterations to the windows in the early nineteenth century.

A possible relic from the early church were the small pointed niches in the spandrels of the south arcade, described and illustrated in E. J. Carlos’ account of the building in The Gentleman’s Magazine, 1832. Carlos was unable to explain these, but they could have been remains of small windows, perhaps of twelfth or early thirteenth century date, which were partly blocked when the arcade was cut through the south wall.

Any early windows in the north wall are likely to have been destroyed when later windows were inserted. All the medieval windows, except for the west window in the tower, were lost when large round-headed windows with plain glazing were inserted at the beginning of the nineteenth century, but their character is apparent in the older views.

The windows in the north wall, two of those in the south wall, and the two east windows were all of the same type: of three uncusped lights, with mullions running up to a depressed arch protected by a hood-mould. This simple type of Perpendicular tracery was a popular fifteenth century form for walls with low eaves where there was no room for elaborate upper lights. It can be seen for example in the City of London at the small church of St Olave Hart Street.

The apparent uniformity of these windows suggests that a general re-windowing programme may have taken place when or after the south aisle was added. On the north side the windows are not placed centrally between the buttresses; possibly they were insertions in an earlier wall. The arrangement in the south wall is more regular, although there are two exceptions: the straight-headed three-light window at the east end of the south wall and the two-light window west of the south porch.

Compared with other fifteenth century building in and around London, the work at Hornsey was old-fashioned, reflecting modest resources and ambitions on the part of the donors.

Get the book

Ivy Mantled Tower by Bridget Cherry is on sale for £7.50 plus p+p using the order form or available in the Old Schoolhouse once we reopen.

Image credits

Distant View of Hornsey Church by J Clennell – HHS;

Hornsey Church from the south-east by Thomas Prattent, The European Magazine 1797 – Bridget Cherry.