In the first of an occasional series of personal reminiscences, journalist Richard Woods shares his memories of writing for the Hornsey Journal in the 1960s.

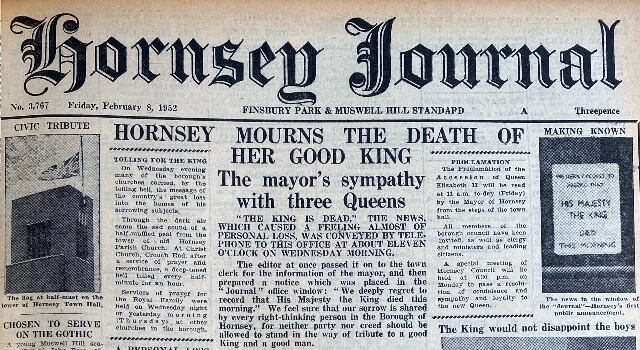

Before the 1970s and 1980s every town had its own local newspaper, even if they were often in group ownership within the county or other regional area. And every newspaper had its own editor. When I joined the Hornsey Journal in the last months of 1960. I had been reading it every week for most of my teenage years. I was 17 and about to become an indentured apprentice reporter for just over four years.

The paper and the community

I was quickly taught how important the paper was to the community – after all there were, I was told, 58,000 houses in Hornsey alone and we served a wider area into areas such as Finchley, Wood Green, Tottenham and more. And we sold just on 60,000 copies each Friday. And this importance was also clear from the content. If it had happened it was in there. If it was going to happen it was advertised. If it was for sale it was advertised. Births, marriages and deaths (BMDs) had their very own page shared with public notices (PNs) and legal stuff. If it was new it was in there and advertised. If it had gone, closed, or changed it would be there. What this content looked like and what actual content the news had was up to the editor and that made him (rarely her back then!) almost as important as the publication itself.

Newsgathering

So to start looking back I will begin with the newspaper. The Hornsey Journal when I joined was a 48-64 page publication. All in black and white and pretty boring by today’s standards. Even headlines were small and the text could easily defeat the elderly, who might be seen in the libraries poring over copies with their magnifying glasses (spectacles being too expensive for many).

On the Journal, reports tended to be long and very detailed. We would even gather the names of mourners at funerals of the better known or important people. This was a chore so deeply horrid that it was always given to the newest or youngest member of staff. Me for a while! Pitman shorthand was essential – especially with an editor like ours who was a supreme expert at it and believed in the ‘verbatim’ report – every word. Fortunately for some councillors he did permit some adjustment for comprehension.

The gathering of material for publication started the moment the last edition had been sent to the presses. That was when we would go through the proof copies of the BMD and PN pages. In those days with no access to local council committees this was often the first place we knew of some planning and other applications. Sometimes the receptionist would take details of some advert, realise its importance and give us an early tip off. We would also scour through the adverts for every event we had not been alerted to.

The diary

Which brings me neatly to ‘the diary’, the bible that ruled every newsroom. This was where all our ‘jobs’ for the week ahead were listed and our initials appended by the chief reporter to cover the event. I have to admit I assumed at first that buttering up said man might be useful to avoid difficult assignments but I soon discovered his system was completely random and thus fair.

I said earlier the style of the newspaper was determined by the editor and so it was. He set the tone of the Journal back then and it was serious, complete to the point of fastidiousness, and respectful. We were set high standards and were often in the local library checking facts or even using their kind offices by telephone!

The working week

We worked long hours in a way, although we were never clocked in or out, unlike the printers down below. We started at about 8.30am Monday to Friday. Nominally office work finished at about 5 pm but we covered everything so evening events and meetings were usually attended and most of us would have an ‘evening job’ assigned on the diary. Dday’s end was highly variable and could extend to beyond 10pm. Sometimes we would do more than one. A few would be marked PU/initials – meaning the person initialed should pick up details later. We were expected to write up our evening jobs by about 9 a.m. the following day.

Friday was different. The paper published that day so the morning would often be consumed by reaction – including the walk ins. These were complaints about content or lack of it. I got a reputation for being a good conciliator, so I was often sent down for these in between the filing job. Filing involved the editor cutting up the paper and marking everything he wanted filed. We (me too often) then assembled this with the picture plates and inserted them or made new files. Friday was also a half day because we all worked Saturday morning. And so Friday was a treasured lunchtime in a pub. Our editor was teetotal so it was the reporters who went to the Bird in Hand, The Kings Head in Crouch End or the Spaniards at Hampstead.

The weekend was rostered so if you were ‘on’ you got a day off in the week. If Saturday was busy, and it often was, then more than one reporter would be at work and you could get several jobs to attend – mostly sales and bazaars. And sport – there was a sports editor but key matches were also covered by reporters. The sports editor did Spurs or Arsenal if at home or maybe Saracens rugby. I was Sports Editor for a year and enjoyed the privilege of being in the press box at these matches.

Another reason why the local newspaper was important – it often provided one of the largest businesses in the town, delivering decently paid employment to many. The Journal employed about 80-100 people in total in the works at 161 Tottenham Lane. A couple were part-time press crew who worked a few hours Thursday to run the press, printing the Journal and its stablemates.

Advertising

And now another crucial element – the advertisements. The first thing to share is the fact that if you are sociologist you will learn more about a location from its local newspaper advertising than its editorial. There are clues to jobs, earnings, shopping, housing, daily life and more. Editorial tells you about failure mostly and a little success.

In those days the local newspaper was the only source available to tell the world about births, weddings, funerals, sales, events, business and more. Much of this went into the ‘classified’ columns, the small ads which the free newspapers stole away as an offering that effectively crucified the paid-for-papers. In my day this constituted as many as eight pages of nine columns of dense but categorised advertisements. I have done a quick calculation. Each column was probably worth £50 in 1960. Being conservative let us say 60 columns. That is £3,000 every week just for those pages. The wages bill for the entire Journal newsroom for example would have been about £150 a week.

There was of course more. In fact, of a 48 page paper, it would be expected that some 30 pages would be advertising. Two pages and sometimes more would be *BMDs (Births, Marriages and Deaths), *PNs (Public Notices) and other local important and legal notices. A lot would be local businesses advertising their wares, their vacancies, their developments and services. And finally the big stuff – national and regional businesses booking space in groups of newspapers, including the Journal.

So I rest my case, as I heard too often from the press benches – back in the day local newspapers like the Hornsey Journal were truly important to their communities.