“I was all knocked up!”, said my 90-year old neighbour. This shocked me at first, but then I realized she meant she was exhausted after a flood of visitors.

A few years ago, when trying to buy a hat in Oxford Street, I found many of the store staff – even supervisors – did not know the word ‘millinery’, and I was loudly derided by two supermarket employees when I suggested flour might be found among the cereals; their only use of the word was in conjunction with ‘breakfast’. I began to think of words and expressions I had grown up with whose meaning has altered or which no one seems to use any more.

The explanation is, of course, that as our lives have changed, formerly commonplace items have disappeared from our homes and from our vocabulary. For example, a kitchen or scullery in my youth often contained a kitchen cabinet, a gas stove, a safe (for food, not valuables), a coal cupboard, a copper, mangle and washboard, a clothes horse and Sunlight Soap. The table might be covered in Serota and the floor in oilcloth. The walls would probably be distempered. Vacuum cleaners, for those lucky enough to own one, were Hoovers, and refrigerators were all Frigidaires. In my parents’ bedroom there was a cheval mirror and chamber pot cupboard and the clothes hung on ‘sticks’, rather than hangers. Some older people had washstands.

In the front room, best room or parlour you could have noted a wireless (running on accumulators which required changing regularly), gramophone, a chair-bed, a china cabinet and a fireplace protected by a fender with fender-seat and/or a fireguard or fire screen. Upholstered items were covered with rexine, and then, later, as people got more prosperous, uncut moquette. The floor-covering was lino with one or two mats and a carpet runner. The coal scuttle would contain Brights or, if times were hard, nuts or coke. The poker was in constant use to shake up the embers, and on winter afternoons the toasting fork was much in evidence, while my dad would “take a kip” on a Sunday after dinner (not lunch which was a pack of sandwiches he took to work to eat mid-morning).

For paraffin and chandlery we went to the oil-shop, our shoes were mended at the boot maker’s (or in some districts the snob’s) and sometimes the coalman came with his horses and the rag and bone man called out, “Old rags and lumber!”. I was sent to buy butter and cheese at a little Welsh shop known as the dairy and we had our hair cut at Regent Saloons or Maison Richard (not the Hairport or Curl up and Dye). The hairdresser would ask if my mother wanted a roll, a pageboy, sweeps or a Eugene perm, and she would use hair pins, clips and setting lotion and sometimes a hairnet.

On a rainy day if my aunt came to visit she would peel off her galoshes at the door, and in winter showy relatives would proudly show off a fox fur, or coat of beaver lamb, Persian lamb or even astrakhan. In the summer my mother’s dress could be of crepe-de-chine, raie-de-chine, morcaine or art silk, and for a wedding she might buy a gown made of silver or gold lame. When I was allowed to wear stockings (rather than socks) they were of lisle or rayon. I remember the day I boldly bought my first fully-fashioned nylons. At school we wore gym slips and for games our footwear was plimsolls.

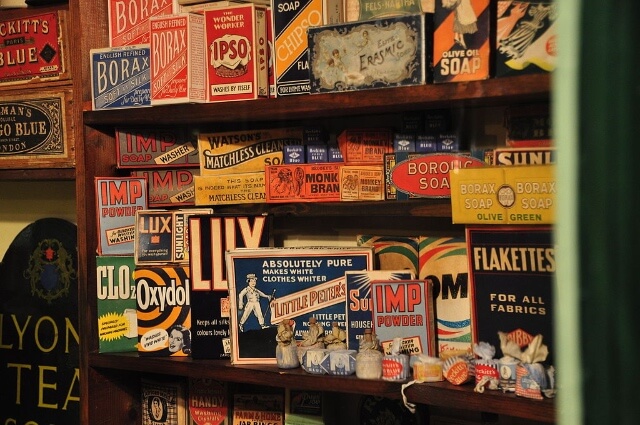

I am sure many people remember the names of familiar household and toilet products; Zebo for the black hearth, Silvo for the brass, Mansion Polish for the furniture, Oxydol to wash the clothes, Scrum to scour the sink, Kolynos toothpaste, Icilma, Amami or Evan Williams shampoo powders in small packets, or Drene, the first liquid one. When we started getting interested in makeup, the brands I remember were Bourjois, Ponds, Outdoor Girl (still with us) and Snowfire (in tiny tins at Woolworth’s), Three Flowers, Richard Hudnut, Gala, Grossmith, Goya, Tangee and Tokalon.

Many expressions, too, have almost disappeared. Some may be very local, but as a Londoner, I remember people saying that a crowded place was mobbed, a dirty, untidy place was a dust hole, and something over-decorated was a poppy show. If someone made a quick get-away, you couldn’t see her for dust. When people were fed up they got the hump, a person with a flashy style was lairy. People put on airs were called, ‘Lord or Lady Dunnabunk’, and were described as swanking or being high hat.

We went very often to the pictures or to a picture palace, or the flicks, and also to the theatre in the gallery (the Gods), the balcony or the pit to see variety, or turns. The comment of an actress in a dramatic role (usually Bette Davis!) would be, “She took a good part”. For something special we went “up west”, not “into town”, because after all, we were already “in town”. In the big stores we travelled on the moving stairs, not an escalator, and we were aware of an important-looking staff member called the floor walker. The staff who today are unaware of millinery, might also have trouble with hosiery, haberdashery and notions.

About the author

Marlene is the author of Lost Theatres of Haringey, Hornsey Historical Society, 2007, and Alexandra Palace Theatre, Hornsey Historical Society, 2013. Both books are in stock and can be purchased through this website.