Recycling a new idea? No, over a hundred and fifty years ago our Hornsey predecessors had organised the recycling of their domestic waste in an impressive way on part of what is now Smithfield Square.

Making money out of dust

Victorian London ran on coal. Domestic dwellings were heated by coal fires, coal was needed to make the steam which powered machinery and for the engines which pulled the carriages and trucks on the miles of railways connected London with the rest of the country. It was estimated that every London household burned 11 tons of coal annually. What was to be done with the resulting ashes and trash residue – all that dust?

Private dust contractors, like wealthy Mr Boffin in Charles Dicken’s novel Our Mutual Friend, made a good living from selling dust and other household waste. They employed dustmen who drove wagons through the streets ringing a bell alerting householders to bring out their dustbins. The mountains of dust were collected in dust yards where it was sifted and sorted to be sold as fertilizer and for bricks. Any metal, rags and bones found profitable uses also.

When a Local Board of Health was set up in Hornsey in 1867 to raise the standard of public health, local dustmen paid the Board for the right to collect dust. Hornsey’s population increased dramatically in the years that followed and the amount of dust and rubbish rose accordingly. The Local Board, wanting to save Hornsey rate payers money by recycling as much refuse as possible, decided to contract the dustmen and to sell the dust to brickfields for a shilling (5p) a cartload; any other salvageable items were sold to dealers. The dustmen proved unreliable and complaints from residents rose year on year.

Hornsey’s dust destructor

The Local Board came up with a plan. It would employ its own dustmen and dispose of the refuse by burning it. Thomas de Courcy Meade, the Board’s Engineer and Surveyor, designed an incinerator called a refuse destructor. It was built at the Board’s new sanitary depot, opened in 1886, behind and to the west of Allen’s Court and Preston’s Court and the shops in front on Hornsey High Street (see Smithfield Square’s Fascinating Past: 1). The destructor was opened with great ceremony on 13th December 1889. It had a 217 foot (66 metres) high chimney which stood on the north side of the boiler house.

This was now the dominant building in Hornsey High Street. There were six furnaces fed by hoppers into which the cartloads of refuse were tipped. The burnt rubbish produced a relatively small amount of clinker that was ground into various grades of grit. This was used by the Local Board as building mortar and concrete. Some of it was used to fill and decorate the walls of the new streets of houses. Some of these walls still stand, testament to the durability of this recycled material. The coarsest grit was used for road making. All this new building material could be sold for profit.

The Hornsey destructor was the first in London sparking great interest from Local Boards around. Although unsavoury, the destructor was recognized as an important contributor to raising standards of public health. It was enlarged from time to time to cope with increasing volumes of refuse and to increase the Board’s income.

Hornsey pioneers new ways of recycling

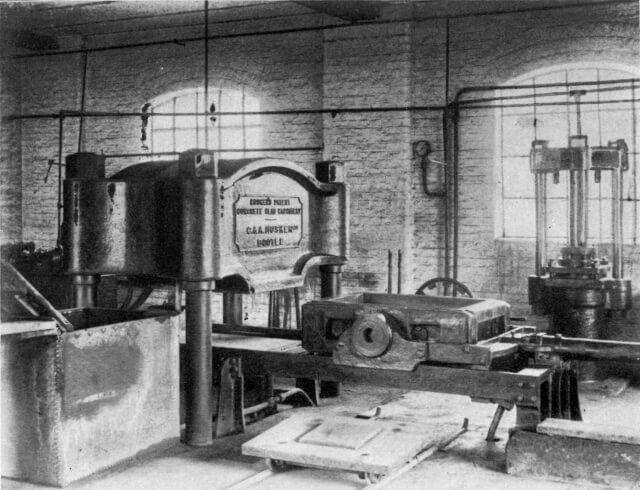

The Local Board was replaced by an Urban District Council in 1895 as Hornsey’s population grew. A new Engineer and Surveyor, Edwin James Lovegrove, was appointed. In a pioneering development at the Hornsey Sanitary Depot, Lovegrove extended and patented the use of the refuse destructor’s clinker in the production of paving slabs and he patented a process for producing clinker asphalt.

Lovegrove also developed machinery and methods at the Hornsey depot for testing the hardness and suitability of various stones in road making. These ideas were taken up by the National Road Board and adopted by the National Physical Laboratory in the development of international standards. Modifications to the Hornsey destructor provided further patents for the separation and recycling of tin and solder from waste tin cans.

As a result of Lovegrove’s work the Hornsey destructor plant and testing laboratory became a focus of attention for public health engineers and road builders everywhere.

John Hinshelwood