The death of a famous Chinese magician as the result of an accident at the Wood Green Empire in the spring of 1918 provided a hot topic for discussion in north London and beyond. The reporting of the inquest in newspapers such as the Bowes Park Weekly News did nothing to halt speculation that the death had not been an accident.

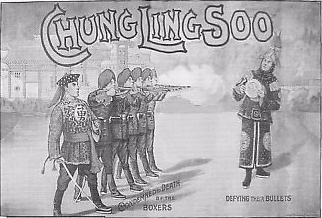

During the second performance at the Empire on 23rd March, Chung Ling Soo’s famous trick ‘Defying the Bullets’ went wrong. He collapsed on stage having been shot and died the next morning at Wood Green Hospital.

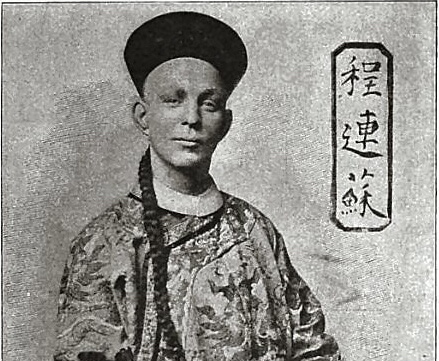

What many of Chung’s legions of fans hadn’t realised was that he wasn’t Chinese at all but an American citizen from Westchester, New York with no Asian heritage, named William Elsworth Robinson. His manufactured identity and complicated personal life probably contributed to the rash of rumours and conspiracy theories that followed his death. As the Bowes Park Weekly News reported, “The most wild and extravagant speculations have been made about the case, and the Coroner received an anonymous letter which he refused to even read.”

Early years

Robinson’s professional life began in the mid-1870s when he was 14, performing on Vaudeville as an illusionist. He progressed in the world of magic and worked for famous magicians including Alexander Herrmann and Harry Kellar but his ambition was to be a headlining act in his own right. His performances as ‘Achmed Ben Ali’ and ‘Robinson the Man of Mystery’ didn’t spark the audiences’ imagination and the huge acclaim he longed for eluded him.

Robinson wasn’t hugely popular with his fellow performers either. Early in his career, he caused controversy by writing a book that revealed the tricks used by illusionists whose performances involved contacting the spirit world. Spirit Slate Writing and Kindred Phenomena was published in New York in 1898 and caused considerable outrage.

The magician reinvented

Accounts vary as to how Robinson came to adopt his Chinese persona. Some say that he answered an advertisement for a Chinese magician with the Folies Bergere in Paris, others that he picked up on the craze for oriental magicians while still in the US. However it happened, Robinson moved to Europe at the end of the 1890s and reinvented himself as Chung Ling Soo, having studied the work of Ching Ling Foo, a popular Chinese illusionist. This move brought Robinson the success he had craved.

Robinson darkened his skin with greasepaint and put his hair into a ‘queue’ – shaved at the front with a plait at the back. He rarely spoke on stage, using broken English when he did and communicated through an interpreter in interviews. His rival Ching Ling Foo seems to have objected to the fact that so much of his material was being incorporated into Robinson’s act. There were public challenges that may have been designed to increase ticket sales but there doesn’t seem to have been a face-to-face standoff. Some held the view that the feud was nothing more than a publicity stunt.

Complicated private life

Robinson’s personal life was complex. He married Bessie Smith in 1883 while still in the US and had a daughter in the same year with another woman. Bessie remained in the US when Robinson moved to Europe but they never divorced. Despite the evidence given at the inquest, he was therefore never legally married to his ‘wife’ and stage assistant Olive Robinson. They were apparently together for twenty years but, as mentioned in the report, she lived in Courcey Road, Wood Green and he lived in Barnes in south-west London.

What wasn’t mentioned in the article was that since 1911 and quite possibly earlier, he had shared the house in Barnes with his three children and their mother, Janet Louise Blatchford. Some reports suggest that Janet was the wife of Robinson’s stage manager but there is no evidence of this. Olive Robinson did live on the same street in Wood Green as Robinson’s manager, Fucado Kametaro, and this may have prompted some speculation. The Probate Calendar for 1918 records that Robinson left all his money (£5831 10s 7d) to Janet.

Rumours and conspiracy theories

As the report shows, the inquest verdict was one of “death by misadventure” but Robinson’s complicated personal and professional life paved the way for many theories that the death wasn’t accidental. Suggestions included that Robinson was in debt and had taken his own life, that his wife was having an affair with his agent and that either one of them or a professional rival had manipulated the gun. William Robinson’s death was as mired in controversy as his life had been.

Image credits

‘Defying the Bullets’ poster – Mike Hazeldine Collection. Chung Ling Soo c. 1906 – Commons Wikimedia Olive Robinson – Flickr / Creative Commons